It’s freezing cold and the sun set over an hour ago, but that doesn’t stop Lindsey Petersen Swan. “Fired up!” she screams at a group of about a dozen teens. “Ready to go!” they holler back.

It’s a Thursday night at the Obama campaign office, and Lindsey and I are keeping an eye on the teens while they parade outside the office, a display intended to attract the attention of traffic passing by on Ingersoll Ave. The kids have signs, noisemakers and giant letters spelling out “Vote Early.” Despite the frigid temperatures, one girl wears shorts and doesn’t even have a coat on – she claims not to be bothered by the cold.

Lindsey turns to me and laughs at the spectacle: a dozen or so excited teens and and the two of us whooping and making noise in the darkness. “I’m just a big kid,” she says.

Lindsey and her sister Leslie were raised in Clear Lake, Iowa, about a two hour drive north of Des Moines. “To me, it wasn’t weird to have politicians in my house,” Lindsey said. Her parents, Dick and Marlene Petersen, were involved in Democratic politics in Iowa and nationally. Lindsey’s house was constantly the staging area for canvass shifts and phone banks.

Lindsey’s father was a stern taskmaster. “It wasn’t ‘Do you want to call?'” Lindsey said. “It was ‘Here’s your packet.'”

Leslie, though two years younger, was more outgoing and willing to talk to strangers – “I was always kinda nervous to call,” Lindsey said. The girls would go door to door together on cold days, then return to the house for a bite to eat. “I remember going to get a bowl of chili from a crock pot after we’d finished out canvass shift,” Lindsey said. “Everybody else would be tired and hungry. We’d be ready to go.”

Gangnam Style is what the kids are listening to these days – a catchy, viral Korean pop song from artist PSY, who performs a “horse dance” in the nonsensical music video. Lindsey and two teenage girls watch the video while we take a break from the cold and get something to eat. Lindsey tries to teach the dance to two sisters, 16-year-old Ashlin Alex and 13-year-old Zoey Wagner. “Left, left, right, right, left, right,” she says while whirling a pantomime lasso. The girls think this is hilarious.

“Stepping into this house is like stepping into a time warp,” Lindsey says.

When Lindsey was in school, she invited Dick Clark, then the junior senator from Iowa to speak to her government class. Her classmates pooh-pooed the idea that a sitting U.S. senator would be addressing them, but they were soon proven wrong. “I introduced him as ‘my friend,'” Lindsey said. Her schoolmates were soon sucked into politics as well. “All my friends were happy because I got them out of school to canvass,” Lindsey said.

On January 17, 1971, South Dakota Senator George McGovern announced he would run for President of the United States. Known for his fierce opposition to the raging Vietnam War, McGovern would eventually win the Democratic primary with a platform of economic populism and grassroots organizational techniques.

McGovern’s campaign was badly damaged, though, by the revelation that his pick for vice president, Thomas Eagleton, had undergone electroshock treatment for depression. This wasn’t acceptable to the American public and Eagleton was forced to resign from the race. Compounding McGovern’s embarrassment, five prominent Democrats refused McGovern’s offers to become his new vice presidential nominee. In McGovern’s own words, the damage to his campaign was “catastrophic.”

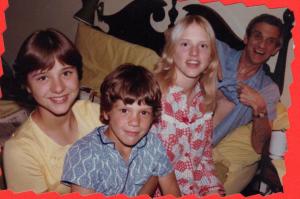

But all nine-year-old Lindsey Petersen knew was the rush of campaigning for the first time for a man who stood for the poor and against Vietnam. At Dick and Marlene’s house, “We actually did have a computer,” Lindsey said. “It printed on those green and white spool papers.”

Lindsey and Leslie were younger than everyone else involved, but her house was filled with “cool people who were older than us who we could talk to,” she said.

“I remember watching the election returns from the campaign headquarters,” she said. McGovern lost the Electoral College to Richard Nixon by a score of 520-17, horrifying Lindsey and Leslie. “We were absolutely devastated.”

Inside the Obama headquarters, a boy named Carlos with an enormous Afro is putting the finishing touches on a posterboard sign. He had drawn a gigantic O, intended to be the first letter of Obama Volunteers, but hadn’t fully considered how the rest of the phrase could fit on the paper. “Dude,” Lindsey says, “where are you going to put the ‘volunteers?'” Lindsey asks him. “He was all enthusiastic with his O,” she tells me, pointing to the “bama volunteers” in tiny script following the O.

Lindsey’s involvement in the 2012 campaign started with the chance decision to attend an Obama rally earlier this summer. While she was picking up her ticket before the rally, she struck up a conversation with the young woman manning the ticket distribution table. It had been over 30 years since Lindsey had been involved in any campaign, but she remembered how much fun it had been as a kid. The young woman held a quick and whispered consultation with a colleague, then gave Lindsey a pair of red VIP tickets, tickets that would get her much closer to the president. “Maybe this will convince you to come volunteer again,” the young woman said.

Dick Petersen, Lindsey’s father, died in February of 1977, the victim of a massive and unexpected coronary on his daughter’s sixteenth birthday. During his eulogy, Lindseyfound out that he had decided to make a bid for U.S. Senate just a few weeks before he died. Her uncle and her father talked over the plan while the family was snowed in during the days that followed Jimmy Carter’s inauguration.

Her mother, who had been a campaign manager and a tireless activist, stepped back from such heavy involvement. “She just lost her passion for politics,” Leslie said of her mother. Five years later, Marlene died at a young age, too. Leslie was still in her teens.

“That’s when I stopped doing political stuff,” Lindsey said. Whenever she’d have offers to get involved in other campaigns, she would pull back. “No,” Lindsey would tell them. “I just can’t.”

Most mornings, either Lindsey or her husband browses the news online as soon as they wake up. It was Lindsey’s turn to look a few weeks ago when she discovered McGovern had died. “It seems really poignant that this is the election I got involved again,” she says. “I think there is a circularity to these things.”

NIce.